How Long Did Rumpelstiltskin Sleep

| Rumpelstiltskin | |

|---|---|

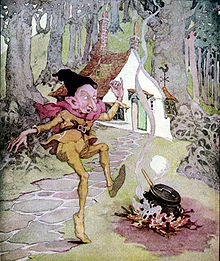

Analogy from Andrew Lang's The Blue Fairy Book (1889) | |

| Folk tale | |

| Proper name | Rumpelstiltskin |

| Also known as |

|

| Data | |

| Country |

|

| Published in |

|

"Rumpelstiltskin" ( RUMP-əl-STILT-skin;[1] German: Rumpelstilzchen) is a High german fairy tale.[2] It was collected by the Brothers Grimm in the 1812 edition of Children's and Household Tales.[2] The story is about a trivial imp who spins straw into golden in exchange for a daughter's firstborn kid.[2]

Plot [edit]

In order to appear superior, a miller brags to the male monarch and people of the kingdom he lives in by claiming his daughter can spin straw into golden.[note 1] The king calls for the girl, locks her upward in a tower room filled with straw and a spinning bike, and demands she spin the straw into gold by morning or he will take her killed.[annotation 2] When she has given up all hope, a little imp-like man appears in the room and spins the straw into gold in return for her necklace. The next morning the king takes the girl to a larger room filled with straw to repeat the feat, the imp once again spins, in return for the daughter's ring. On the 3rd day, when the daughter has been taken to an fifty-fifty larger room filled with straw and told by the king that he will marry her if she can fill this room with gold or execute her if she cannot, the girl has nothing left with which she tin pay the strange brute. He extracts a promise from her that she will give him her firstborn child, and so he spins the straw into gold a final time.[note 3]

Illustration by Anne Anderson from Grimm'due south Fairy Tales (London and Glasgow 1922)

The rex keeps his promise to marry the miller's daughter. But when their outset child is born, the imp returns to merits his payment. She offers him all the wealth she has to go on the child, but the imp has no interest in her riches. He finally agrees to give up his merits to the child if she can guess the imp'due south name within three days.[note iv]

The queen'due south many guesses fail. But before the final night, she wanders into the woods[note v] searching for him and comes beyond his remote mount cottage and watches, unseen, equally he hops virtually his burn and sings. In his song's lyrics—"this evening tonight, my plans I make, tomorrow tomorrow, the infant I have. The queen will never win the game, for Rumpelstiltskin is my proper name"—he reveals his name.

When the imp comes to the queen on the third day, after first feigning ignorance, she reveals his name, Rumpelstiltskin, and he loses his atmosphere at the loss of their bargain. Versions vary about whether he accuses the devil or witches of having revealed his name to the queen. In the 1812 edition of the Brothers Grimm tales, Rumpelstiltskin then "ran away angrily, and never came dorsum." The catastrophe was revised in an 1857 edition to a more than gruesome ending wherein Rumpelstiltskin "in his rage drove his correct foot and so far into the ground that it sank in upward to his waist; and then in a passion he seized the left human foot with both easily and tore himself in ii." Other versions have Rumpelstiltskin driving his right pes then far into the basis that he creates a chasm and falls into information technology, never to exist seen again. In the oral version originally nerveless past the Brothers Grimm, Rumpelstiltskin flies out of the window on a cooking ladle.

- Notes

- ^ Some versions brand the miller'due south girl blonde and describe the "straw-into-aureate" merits as a careless boast the miller makes nigh the way his girl'southward harbinger-like blond hair takes on a gold-similar lustre when sunshine strikes it.

- ^ Other versions take the king threatening to lock her upwardly in a dungeon forever, or to punish her father for lying.

- ^ In some versions, the imp appears and begins to turn the harbinger into aureate, paying no mind to the daughter's protests that she has nothing to pay him with; when he finishes the job, he states that the price is her first child, and the horrified girl objects because she never agreed to this organization.

- ^ Some versions take the imp limiting the number of daily guesses to 3 and hence the total number of guesses allowed to a maximum of nine.

- ^ In some versions, she sends a retainer into the woods instead of going herself, in order to go on the king's suspicions at bay.

History [edit]

Co-ordinate to researchers at Durham Academy and the NOVA University Lisbon, the origins of the story can be traced back to around 4,000 years ago.[ undue weight? ] [3] [4] A possible early on literary reference to the tale appears in Dio of Halicarnassus' Roman Antiquities, in the 1st century CE [five]

Variants [edit]

The same story pattern appears in numerous other cultures: Tom Tit Tot [6] in United Kingdom (from English Fairy Tales, 1890, by Joseph Jacobs); The Lazy Beauty and her Aunts in Ireland (from The Fireside Stories of Ireland, 1870 by Patrick Kennedy); Whuppity Stoorie in Scotland (from Robert Chambers's Popular Rhymes of Scotland, 1826); Gilitrutt in Iceland;[seven] [8] جعيدان (Joaidane "He who talks too much") in Standard arabic; Хламушка (Khlamushka "Junker") in Russia; Rumplcimprcampr, Rampelník or Martin Zvonek in the Czech Republic; Martinko Klingáč in Slovakia; "Cvilidreta" in Croatia; Ruidoquedito ("Little noise") in South America; Pancimanci in Hungary (from 1862 folktale collection by László Arany[ix]); Daiku to Oniroku (大工と鬼六 "The carpenter and the ogre") in Nippon and Myrmidon in France.

An earlier literary variant in French was penned by Mme. L'Héritier, titled Ricdin-Ricdon.[10] A version of information technology exists in the compilation Le Chiffonier des Fées, Vol. XII. pp. 125-131.

The Cornish tale of Duffy and the Devil plays out an essentially similar plot featuring a "devil" named Terry-top.[11]

All these tales are classified in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index every bit tale blazon ATU 500, "The Proper name of the Supernatural Helper".[12] [13] According to scholarship, it is popular in "Kingdom of denmark, Finland, Germany and Ireland".[xiv]

Proper name [edit]

Analogy by Walter Crane from Household Stories by the Brothers Grimm (1886)

The name Rumpelstilzchen in German (IPA: /ʀʊmpl̩ʃtiːlt͡sçn̩/) means literally "little rattle stilt", a stilt being a post or pole that provides support for a structure. A rumpelstilt or rumpelstilz was consequently the name of a blazon of goblin, also called a pophart or poppart, that makes noises by rattling posts and rapping on planks. The pregnant is similar to rumpelgeist ("rattle ghost") or poltergeist, a mischievous spirit that clatters and moves household objects. (Other related concepts are mummarts or boggarts and hobs, which are mischievous household spirits that disguise themselves.) The ending -chen is a German diminutive cognate to English -kin.

The name is believed to be derived from Johann Fischart'south Geschichtklitterung, or Gargantua of 1577 (a loose adaptation of Rabelais' Gargantua and Pantagruel), which refers to an "entertainment" for children, a children'southward game named "Rumpele stilt oder der Poppart".[15] [ unreliable source ]

Translations [edit]

Illustration for the tale of "Rumpel-stilt-peel" from The heart of oak books (Boston 1910)

Translations of the original Grimm fairy tale (KHM 55) into various languages have generally substituted dissimilar names for the dwarf whose proper name is Rumpelstilzchen. For some languages, a proper name was called that comes close in sound to the German name: Rumpelstiltskin or Rumplestiltskin in English, Repelsteeltje in Dutch, Rumpelstichen in Brazilian Portuguese, Rumpelstinski, Rumpelestíjeles, Trasgolisto, Jasil el Trasgu, Barabay, Rompelimbrá, Barrabás, Ruidoquedito, Rompeltisquillo, Tiribilitín, Tremolín, El enano saltarín y el duende saltarín in Spanish, Rumplcimprcampr or Rampelník in Czech. In Japanese, information technology is called ルンペルシュティルツキン (Runperushutirutsukin). Russian might have the virtually achieved simulated of the High german proper noun with Румпельшти́льцхен (Rumpelʹshtílʹtskhen).

In other languages, the name was translated in a poetic and approximate style. Thus Rumpelstilzchen is known as Päronskaft (literally "Pear-stalk") in Swedish,[16] where the sense of stilt or stalk of the second role is retained.

Slovak translations use Martinko Klingáč. Shine translations apply Titelitury (or Rumpelsztyk) and Finnish ones Tittelintuure, Rompanruoja or Hopskukkeli. The Hungarian proper name is Tűzmanócska and in Serbo-Croatian Cvilidreta ("Whine-screamer"). The Slovenian translation uses "Špicparkeljc" (pointy-hoof). For Hebrew the poet Avraham Shlonsky composed the name עוץ לי גוץ לי (Ootz-li Gootz-li, a compact and rhymy touch to the original sentence and meaning of the story, "My adviser my midget"), when using the fairy tale as the ground of a children'due south musical, now a classic amongst Hebrew children's plays. Greek translations have used Ρουμπελστίλτσκιν (from the English) or Κουτσοκαλιγέρης (Koutsokaliyéris), which could figure equally a Greek surname, formed with the particle κούτσο- (koútso- "limping"), and is perhaps derived from the Hebrew name. In Italian, the creature is usually called Tremotino, which is probably formed from the world tremoto, which means "earthquake" in Tuscan dialect, and the suffix "-ino", which generally indicates a small and/or sly character. The first Italian edition of the fables was published in 1897, and the books in those years were all written in Tuscan. Urdu versions of the tale used the name Tees Mar Khan for the imp.

Rumpelstiltskin principle [edit]

The value and ability of using personal names and titles is well established in psychology, direction, teaching and trial law. Information technology is oftentimes referred to as the "Rumpelstiltskin principle". Information technology derives from a very ancient conventionalities that to requite or know the true proper name of a existence is to have power over information technology, for which compare Adam's naming of the animals in Genesis 2:nineteen-20.

- Brodsky, Stanley (2013). "The Rumpelstiltskin Principle". APA.org. American Psychological Association.

- Winston, Patrick (2009-08-sixteen). "The Rumpelstiltskin Principle". MIT.edu.

- van der Geest, Sjak (2010). "Rumpelstiltskin: The magic of the correct word". In Oderwald, Arko; van Tilburg, Willem; Neuvel, Koos (eds.). Unfamiliar knowledge: Psychiatric disorders in literature. academia.edu. Utrecht: De Tijdstroom.

Media and popular culture [edit]

Pic adaptations [edit]

- Rumpelstiltskin (1915 moving-picture show), an American silent moving-picture show, directed by Raymond B. West

- Rumpelstiltskin (1940 film), a High german fantasy flick, directed by Alf Zengerling

- Rumpelstiltskin (1955 moving-picture show), a High german fantasy film, directed by Herbert B. Fredersdorf

- Rumpelstiltskin (1985 flick), a twenty-4-minute animated feature

- Rumpelstiltskin (1987 film), an American-Israeli picture

- Rumpelstiltskin (1995 picture), an American horror motion picture, loosely based on the Grimm fairy tale

- Rumpelstilzchen (2009 film), a German TV adaptation starring Gottfried John and Julie Engelbrecht

Ensemble media [edit]

- Rumplestiltskin appears as a figment of Chief O'Brien'south imagination in the 16th episode If Wishes Were Horses of flavor 1 in the Star Trek series Deep Space 9

- Rumplestiltskin appears as a villainous grapheme in the Shrek franchise, first voiced by Conrad Vernon in Shrek the Third as a background villain recruited by Prince Charming to conquer the kingdom of Far Far Away. In Shrek Forever After, the character's appearance and persona are significantly contradistinct to go the main villain of the film, at present voiced by Walt Dohrn. This version of the character has a personal vendetta against the ogre Shrek, as the latter's rescue of Princess Fiona in the first film foiled "Rumple's" plot to take over Far Far Away. Rumple takes reward of Shrek's growing frustration with parental life, striking a magical deal where Shrek could exist "an ogre for a twenty-four hours", the way things used to be. The deal is struck, and Shrek discovers that Rumple took the twenty-four hours he was built-in, creating an alternating reality where Fiona was never rescued and Rumple ascended to power with the help of an regular army of witches, a giant goose named Fifi, and the Pied Piper. As such, Shrek has 24 hours to reach true-honey'south kiss and intermission the spell, which he does, and Rumple is imprisoned in the chief reality. Dohrn'south version of the character also appears in diverse spin-offs.

- In the American fantasy take a chance drama television series Once Upon a Fourth dimension, Rumplestiltskin is one of the integral characters, portrayed by Robert Carlyle. In the fairytale world of the series, known as the Enchanted Forest, Rumplestiltskin was a cowardly peasant who ascended to ability by killing the "Dark I" and gaining his nighttime magic to protect his son Baelfire. Still, the darkness causes him to grow increasingly twisted and violent, committing evil actions such equally killing Baelfire's mother and cutting off Captain Hook's paw. With the assistance of the Blue Fairy, Baelfire finds a mode to travel to a earth without magic to eliminate his father'southward curse, to which Rumple hesitantly agrees. However, in a moment of weakness, Rumplestiltskin allows Baelfire to autumn through without him. Instantly regretting this, Rumplestiltskin orchestrates a complex, decades-long series of events to find his son: manipulating the Evil Queen into cursing the country by transporting everyone to Earth and wiping their memories to achieve her happy ending, implementing a failsafe in the form of the savior Emma Swan (the daughter of Snow White and Prince Charming), and using the magic extracted from Snow and Mannerly'south union of true honey to bring magic to the real world in order to locate Baelfire, while maintaining his powers. During this procedure, and throughout the series, he wrestles with the disharmonize betwixt his nighttime nature and the phone call to exercise the right thing, and the ramifications affecting his dearest for and eventual marriage with Belle.

- Rumpelstiltskin appears in Ever After High as an infamous professor known for making students spin straw into gold as a form of extra credit and detention. He purposely gives his students bad grades in such a way they are forced to ask for extra credit.

Theater [edit]

- Utz-li-Gutz-li, a 1965 Israeli stage musical written past Avraham Shlonsky

- Rumpelstiltskin, a 2011 American stage musical

See also [edit]

- True name

References [edit]

- ^ Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ a b c "Rumpelstiltskin". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 2020-eleven-12 .

- ^ BBC (2016-01-20). "Fairy tale origins thousands of years old, researchers say". BBC. Retrieved xx January 2016.

- ^ da Silva, Sara Graça; Tehrani, Jamshid J. (January 2016). "Comparative phylogenetic analyses uncover the ancient roots of Indo-European folktales". Royal Lodge Open Science. 3 (1): 150645. Bibcode:2016RSOS....350645D. doi:x.1098/rsos.150645. PMC4736946. PMID 26909191.

- ^ Anderson, Graham (2000). Fairytale in the Ancient World. Routledge. ISBN9780415237031.

- ^ ""The Story of Tom Tit Tot" | Stories from Around the World | Traditional | Lit2Go ETC". etc.usf.edu.

- ^ Grímsson, Magnús; Árnason, Jon. Íslensk ævintýri. Reykjavik: 1852. pp. 123-126. [one]

- ^ Simpson, Jacqueline (2004). Icelandic folktales & legends (2d ed.). Stroud: Tempus. pp. 86–89. ISBN0752430459.

- ^ László Arany: Eredeti népmesék (folktale collection, Pest, 1862, in Hungarian)

- ^ Marie-Jeanne L'Héritier: La Bout ténébreuse et les Jours lumineux: Contes Anglois, 1705. In French

- ^ Hunt, Robert (1871). Pop Romances of the West of England; or, The Drolls, Traditions, and Superstitions of Old Cornwall. London: John Camden Hotten. pp. 239–247.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: Brute tales, tales of magic, religious tales, and realistic tales, with an introduction. FF Communications. p. 285 - 286.

- ^ "Name of the Helper". D. Fifty. Ashliman. Retrieved 2015-11-29 .

- ^ Christiansen, Reidar Thorwalf. Folktales of Norway. Chicago: University of Chicago press by 1994 . pp. 5-6.

- ^ Wiktionary article on Rumpelstilzchen.

- ^ Grimm, Jacob; Grimm, Wilhelm (2008). Bröderna Grimms sagovärld (in Swedish). Bonnier Carlsen. p. 72. ISBN978-91-638-2435-7.

Selected bibliography [edit]

- Bergler, Edmund (1961). "The Clinical Importance of "Rumpelstiltskin" Equally Anti-Male Manifesto". American Imago. 18 (one): 65–70. ISSN 0065-860X. JSTOR 26301733.

- Marshall, Howard W. (1973). "'Tom Tit Tot'. A Comparative Essay on Aarne-Thompson Blazon 500. The Proper noun of the Helper". Folklore. 84 (1): 51–57. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1973.9716495. ISSN 0015-587X. JSTOR 1260436.

- Ní Dhuibhne, Éilis (2012). "The Name of the Helper: "Kinder- und Hausmärchen" and Republic of ireland". Béaloideas. eighty: i–22. ISSN 0332-270X. JSTOR 24862867.

- Rand, Harry (2000). "Who was Rupelstiltskin?". The International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 81 (5): 943–962. doi:10.1516/0020757001600309. PMID 11109578.

- von Sydow, Carl W. (1909). Två spinnsagor: en studie i jämförande folksagoforskning (in Swedish). Stockholm: P.A. Norstedt. [Assay of Aarne-Thompson-Uther tale types 500 and 501]

- Yolen, Jane (1993). "Foreword: The Rumpelstiltskin Cistron". Periodical of the Fantastic in the Arts. 5 (2 (eighteen)): 11–13. ISSN 0897-0521. JSTOR 43308148.

- Zipes, Jack (1993). "Spinning with Fate: Rumpelstiltskin and the Decline of Female Productivity". Western Folklore. 52 (1): 43–60. doi:10.2307/1499492. ISSN 0043-373X. JSTOR 1499492.

- T., A. West.; Clodd, Edward (1889). "The Philosophy of Rumpelstilt-Peel". The Folk-Lore Journal. 7 (2): 135–163. ISSN 1744-2524. JSTOR 1252656.

Further reading [edit]

- Cambon, Fernand (1976). "La fileuse. Remarques psychanalytiques sur le motif de la "fileuse" et du "filage" dans quelques poèmes et contes allemands". Littérature. 23 (3): 56–74. doi:ten.3406/litt.1976.1122.

- Dvořák, Karel. (1967). "AaTh 500 in deutschen Varianten aus der Tschechoslowakei". In: Fabula. ix: 100-104. ten.1515/fabl.1967.9.1-3.100.

- Paulme, Denise. "Thème et variations: l'épreuve du «nom inconnu» dans les contes d'Afrique noire". In: Cahiers d'études africaines, vol. 11, due north°42, 1971. pp. 189-205. DOI: Thème et variations : l'épreuve du « nom inconnu » dans les contes d'Afrique noire.; www.persee.fr/md/cea_0008-0055_1971_num_11_42_2800

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rumpelstiltskin

Posted by: brownthabould.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Long Did Rumpelstiltskin Sleep"

Post a Comment